From Salvage to Salvation

The first time I saw the wooden fishing trawler YUKON she was lying just south of Copenhagen, Denmark. She was a beauty, with sweet lines that set my creative juices flowing. She was big enough to live aboard and, with the correct sail plan, would be manageable by a few people. With a length of 65′ on deck, a beam of 14′, and a draft of 6′, she seemed a perfect fit for a sailing shipwright like me; just the right size to sail around the globe. Unfortunately, she was not for sale. What’s more, she lay at the bottom of Dragør Harbour.

At that time, I had been living in Denmark for only a few months, working as a stagehand. My profession had taken me all over the world, and now I was a long way from Adelaide, South Australia, where I’d been born and raised. There I had done my apprenticeship building sailing dinghies, then worked on the construction of the sail-training brigantine ONE AND ALL.

Now I wanted my own ship.

YUKON’s owners refloated her, and while they emptied the accommodation of waterlogged mattresses and sodden charts and publications, I was able to check her out. I could see that she was just what I had always dreamed of; a true little ship with proper stanchions and bulwarks, hatches and skylights. YUKON had started life as a fishing trawler in the North Sea off Jutland, Denmark, around 1930. By the time I found her, she had had several different owners and had been transformed from a fishing vessel to a pleasure craft. Her current custodians understandably had a passionate attachment to their vessel and had, over the past 15 years, seen their children grow from wearing diapers to make-up, and had cruised the coast and chugged around to the various events that make up the Danish wooden boat calendar.

Six months later, while viewing another boat in Rudkoebing, in southern Denmark, my good Aussie mate Ross Grange rang me and said, “Check the paper.” I got the local newspaper, and there she was: YUKON was for sale—for about double my meager savings. Undaunted, I contacted the sellers. Although they said they would consider my offer, I wasn’t hopeful. But sometimes it’s a case of “ship seeks owner” rather than the other way around.

Two days later, the owners phoned me back and the voice at the other end of the line sounded desperate; YUKON had sunk again in Dragør Harbour. Having salvaged her once, they could not afford to do it a second time.

Taking the Plunge

I went back to have another look. YUKON was clearly tired, and clearly in need of a friend. Ross, with his broad Queensland accent, spoke optimistically of “mates with cranes” and “running a couple of slings ’round her guts.” With his experience in industrial diving, Ross and his plan seemed to be our only chance. My Danish was limited to the standard “I love you” and “two beers please,” so an acquaintance proved most helpful in drafting up a salvage assessment in Danish and English. Under the circumstances, I felt that I really needed to see the boat out of the water to get a true appreciation of her lines.

The salvage operation was fraught with hiccups. I had a full-time job and could only spend weekends and evenings at the project. The floating crane that was supposed to do the job looked like it couldn’t lift a fly, and our pumps were totally inadequate. But after Ross’s many hours of diving to patch suspect leaks and run slings, we secured the use of a bigger crane and an ever-increasing number of helpers.

By the third weekend, we were on the brink of success: we just had to displace a little more water and get her main hatch above the surface. For this third attempt we organized more people to help, including the local fire brigade, who graciously loaned pumps and volunteered their time. Clearly I was not the only one who was intrigued by the little old vessel.

As a final attempt, we chucked both life rafts in the hold, shut the hatch, and inflated them. Yes! What a relief … she was floating! The fire brigade volunteers, owners, friends, and loved ones all gave cheers of delight as the old dame rose off the bottom and presented herself once again to the summer sunshine. It was June 19, 1997.

The clock was ticking: I now had 24 hours to decide whether to take her on. Towing her to the nearest slip meant going through the heart of Copenhagen, including passing through two drawbridges—and traffic would need to be held up at the second one. The following day, a chartered salvage tug took us gingerly on our way. Throughout the three hours’ passage, we cleaned, scraped, and “inspected” the boat. During that trip I also enjoyed the sensation of actually sailing her.

Because it was a lovely day and we had worked so hard to raise YUKON, it felt like we had nearly finished the job. We were exhausted after our hard work, and the 24-hour inspection period was up before we knew it. The old saying “Many a man has fallen in love with a dimple but made the mistake of marrying the whole girl” could have been scripted for this situation. Was I on the verge of making a costly mistake? The owners were getting twitchy: there would be a lot of work to get the boat back into the water, and they wanted to know if they needed to make a start or if they would be able to walk away. I knew that I was looking at a big project, but on the other hand, when would I get another chance to acquire a vessel of this caliber for only a case of beer? And I could see that YUKON was better shaped and better preserved below the waterline than even an optimist like me could have hoped. These Danes sure could build a beautiful boat. “Yes,” I said to the owners. “I’ll take her!”

Never before had I seen such relief on human faces.

I was a happy man, wandering the scaffold around my new vessel, poking her with a screwdriver and finding rot here and there, but generally nothing too extreme.

After three or four days of caulking and painting, we refloated her. Now we had to look for a permanent berth. We were surprised to discover that the only place we were allowed to keep the vessel was in the very heart of Copenhagen, in Nyhavn. I couldn’t believe that the authorities would allow a wreck like mine to sit slap-bang in the middle of one of Denmark’s biggest tourist attractions for only $200 a year.

There is a large fraternity of wooden ship enthusiasts in Denmark. One of these organizations, called TS (Træskibs Sammenslutningen–Wooden Boat Association), has harbors around the whole country, with particular wharves and piers restricted (in theory at least) to member vessels. Luckily, Nyhavn was one of those places. So there I was, shoveling mud, grease, and rotten wood into plastic bags just meters from fine French cuisine and tourists at play. I could feel the eyes of the diners on me, no doubt thinking: what’s this guy doing? The facility was not optimal, but it was sufficient for YUKON’s first stages. Wharf space at Nyhavn was very limited, and rules were fairly strict with regard to storing materials. Luckily I had good deck space, so it was a case of building a bit of a tent onboard and storing everything out of sight.

By now I had a full-time job building the interior of a yacht, a two-year project that provided me with a livelihood. Apart from this, the coast was essentially clear for me to get involved with YUKON’s restoration. I didn’t really have a plan; I had a dream for what I wanted YUKON to be. My dream was to restore the vessel and sail her back to Australia. Even though I came to the job with a lot of experience, I had no idea of how much work and time it would take to fulfill this dream.

Repairing stanchions, for example, was a case of completely destroying the old piece and making a new one. This could be done in a relatively stress-free way because the caprail and covering boards were also in need of replacement, so it gradually dawned on me that there would be very little of the original boat left above the waterline. YUKON’s generous scantlings–2” oak planking on 5” frames–made perfect patterns. All her fastenings were galvanized, or at least they had been 70 years ago. I had to make a decent job of it; there was no other way. I would restore her following the skilled men who had built her originally, but this time I would coat all covered surfaces with red lead and plenty of fungicide.

Danish oak is a fantastic material. In Denmark, there are cultural links going straight back to the Vikings, and one of these is oak. My experience with this hardwood was limited, having trained in South Australia, where a European oak tree was something that stood outside a museum; it wasn’t something you were allowed to cut down and fix old fishing trawlers with.

So, in Denmark, the pleasures were plenty in visiting various sawmills and meeting interesting people—and buying lots of fine Danish oak.

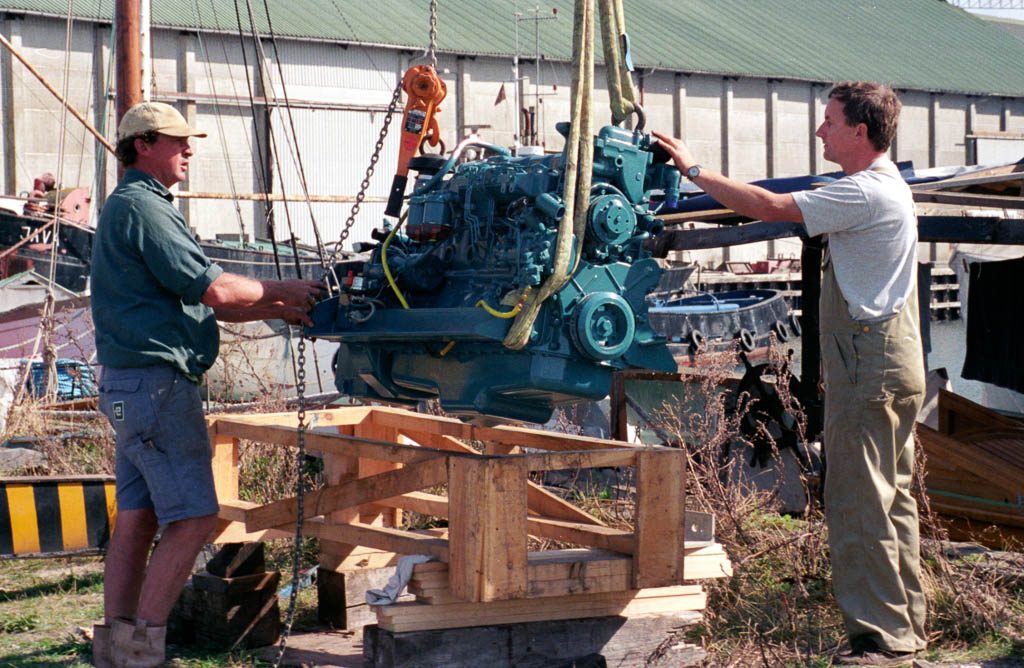

My single-mindedness was not without serious bouts of self-doubt as the extent of the project became increasingly evident. The old main engine, a two-cylinder Alpha diesel (which amounted to 7.5 tons of rust), took up 40 percent of the space below deck, and it would cost more to restore it than to replace it with a new six-cylinder 125-hp Ford diesel. All the electrics, all the plumbing, the entire interior—pretty much everything—would have to be changed or restored.

When I wasn’t actually working onboard YUKON, I was planning, talking, drawing, and thinking YUKON. I made sure I always had a couple of things on the go at once so that I didn’t become too bogged down or discouraged. If one aspect of the job wasn’t going well or my energy levels weren’t up to the task at hand, I could switch to something else for a while. Work on the vessel was proceeding apace when I was suddenly faced with finding another place to live, not always easy in Copenhagen. It was one of those crunch times, when I could just as easily have walked away from the project, headed back to my house in Australia, and put the whole thing down to experience. Instead, I packed my swag, bought a CD player, and moved on board YUKON—starting out with a small ship’s woodstove and a bag of groceries. Fortunately it was summer, and the Danish summers are lovely, with long warm days and scarcely an hour of darkness. And Nyhavn, in the middle of Copenhagen, was not the worst place in the world for a sailor to find himself living, even if it was amidst the remnants of a boat.

I completed my two-year job fitting out the yacht, and signed on as second mate aboard an anchor-handler out of Aberdeen, just across the North Sea in Scotland.

The money was good and I worked five weeks on, five weeks off—perfect for carrying on with YUKON’s restoration. Things went well, and a good stretch of time living aboard YUKON gave me time to think about what I was doing. So long as you are doing the work yourself, it’s just time and raw materials that you need. Drawings and sketches developed, and I could sense that a plan was coming together.

Once while I was working on deck, a young boy inquired as to how much such a vessel would cost. I proudly replied this one had cost me just one case of beer. He looked around at all the beautiful ships in the harbor, looked back at YUKON, and said, “I think you paid too much!” I supposed she must have been a sorry sight, but I could only see the big picture–most of the time. An old friend of mine, Capt. John Soerensen, called me up one day and tried to lure me out of the grime of my engineroom. He spoke of schooners and ketches racing around Funen, one of the largest of the 300 or so islands that make up Denmark. It would take one week, and there would be about 40 vessels participating. He had just purchased the lovely schooner FREIA, built on the island of Bornholm in 1890. She was fast and John was a great sailor, but he needed extra hands to win. He talked me into joining his crew.

This race is an annual event, and one of the premier regattas in the Danish sailing calendar. Many of the charter boats in Denmark meet up and sail together, taking a week off from the hectic sailing season. Over the years it has developed into a major event that attracts large crowds of visitors, both sailing and observing, in all the harbors the fleet visits. It’s something of a circus but great fun. We didn’t win, but I met my life’s love.

Ea was first mate and cook onboard John’s schooner, and there were good vibes from the moment we laid eyes on each other. She had rough hands and soft green eyes, and I was swept away. After I accidentally spilt red wine on her dress, I invited her to Copenhagen so I could buy her a new one. Ea was fascinated not just by YUKON but also by the vessel’s prospects. Luckily for me, our relationship was the real thing.

After a surprisingly short time, Ea contacted me while I was at sea off Aberdeen and informed me that she was pregnant. I was in the middle of a fire drill on the ship and asked if I could call her back in a few minutes. But I didn’t need time to think.

And so my 35 years of footloose freedom came to a delightful halt. Our first son, Kristopher, was born and Ea and I married soon after. I quit my job at sea to concentrate on being a father and husband.

This also gave me the chance to continue construction of YUKON’s two deckhouses. By now YUKON had been towed the 140 miles to the town of Svendborg, one of Denmark’s historic maritime towns and home to one of its famous shipyards, J. Ring-Andersen.

After removing all of YUKON’s interior, I discovered that the inside of her 2” planking, especially around the turn of her bilges, was badly rotted, the result of leaking stanchions. I estimated that I would have to change 200 meters of planking and 50 meters of framing. That was not a good day, but philosophically, I knew that the project was at a turning point. Such an undertaking was daunting. Dealing with 2” oak planking is hard work, and I couldn’t do it alone. It would require far too long out of water, especially with replacing the 5” frames.

Ea said that she didn’t want to spend the first 20 years of our marriage waiting to sail, and I had to agree. The restoration needed to go a bit quicker, and that needed money.

Three times we applied for funding from Denmark’s Wooden Ship Preservation Trust but were turned down each time on the grounds that vessels like YUKON were common and the Trust had already invested large sums in similar ones. We needed to find another solution.

A New Tack

Ea came up a plan for starting a charter business. With her background as a social adviser, and the experience we both had in sail training, we might stand a chance of convincing the bank that we could be a going concern. With a roll of drawings and high hopes, we went to our banker. I don’t know how we did it, but they said yes: they would lend us one million Danish kroner (about US$200,000). We went home joyously, enjoying the fact that for the first and probably only time in our lives, we were millionaires.

Now it was full steam ahead. We approached a couple of yards around the area and decided on J. Ring-Andersen, known the world over among the wooden ship fraternity. This fourth-generation family-run business attracts ships from all the over the Baltic region and with good reason, given its experience, thorough workmanship, and customer-oriented approach.

It was one of those cherished moments, sitting in Peter Ring-Andersen’s meeting room, adorned with half models, discussing our upcoming job. My Danish was still pretty rough, but we managed to agree on a plan. I was allowed to continue to work on our boat alongside the yard’s shipwrights. This was a huge plus, as the deal included use of all machinery and access to all materials, which was much more convenient than going elsewhere to buy things. And, after working more or less alone for three years, I found it a huge morale boost to be working alongside fellow professionals.

While the yard’s shipwrights replaced planks and frames, I managed to renew most of her deckbeams (while our two new deckhouses were more or less hanging in the air) and put in a new stem and counter including all knees except two. The keel and keelson and bottom planking were found to be sound, as were the floors and stringers.

Three months on the slipway drew to a close in the summer of 2001. At her relaunching, YUKON revealed a vessel revitalized and floating a good foot higher. Such a beauty! Her clean lines and healthy aroma below decks inspired us to keep on going. After what could be considered the successful restoration of YUKON’S hull, it was time to turn our attention to her deck and interior. With help from friends and volunteers, we created a living space including a galley, saloon, and aft cabin. This enjoyable but time-consuming work was completed by August 2002.

At last it was possible to move our little family aboard. I’ll never forget our first night, sitting in our lantern-lit saloon with the woodstove burning brightly and surrounded by the fruits of our labors.

After two years at Ring-Andersen’s shipyard, it was time to move on. Our good friend Ziggy Kruger, with his lovely ship ARKONA, offered us a tow to the nearby town of Rudkoebing and the Red Warehouse.

The Red Warehouse is one of those institutions in Denmark that make it possible to undertake a project like ours. It is an old shipping warehouse, standing proudly restored on the quay of this small medieval town. It has been host to scores of wooden ship restorers over the past 25 years.

In all, 27 vessels have benefited from the use of the organization’s workshop and living quarters. It’s a real do-it-yourself place.

Finally, on July 18, 2004, after seven years of hard work, we took our maiden voyage. YUKON was sailing again. This first trip was to Svendborg to take part in YUKON’s first regatta, the round-Funen race. We had done it! Tired but exuberant, we (and all our volunteers) enjoyed a good week’s sailing and had a great time.

Wooden vessels abound with human energy; this is their true beauty. Their pieces are sawn, bent, and carefully laid together. Every turn of a clamp, every bang of a spike, every grunt, every groan … it all remains in them. The reward for all our hard work is the feeling that we have brought YUKON back to life. Since that desperate salvage exercise in 1997, a great many hours have been spent thinking, working, and dreaming. We have now sailed over 14,000 miles in the Baltic Sea, giving almost 1,500 guests the opportunity to learn about sailing traditional craft.

Republished with thanks, from the original in Wooden Boat Magazine.